According to Ian Thomson’s biography of him, the Italian writer Primo Levi visited Liverpool just before Christmas 1971. He went with Maurilio Tambini, the sales manager at the Turin chemical factory where he worked, to buy some enamalled conductors. Levi, who stayed at the Adelphi Hotel, was saddened to see rough sleepers on the Metropolitan Cathedral steps and much of the city still not rebuilt after wartime bombing. But the weather, as now, was unseasonably mild and in the sunshine Levi, who had been suffering from depression, cheered up. He passed on the chance to see Norman Wisdom playing in the panto Robinson Crusoe at the Liverpool Empire, but he did go to the Cavern Club, and on the waterfront he watched Liverpool’s last transatlantic liner, the Empress of Canada, leave on its last voyage to Tilbury docks, with other boats on the Mersey hooting a melancholy farewell.

2015: A found poem

2015 was the year of peak iPhone.

2015 was the year of designer yeast.

2015 was the year that designers said enough with the rigid fashion show system and basta to the industry’s brutal pace.

2015 was the year we all heard of some bright young thing called Neville Brody.

2015 was the year where every respectable underground dance music label released a project inspired by instrumental grime.

2015 was the year of the naked dress.

2015 was the year of the man bun, from the birth of the clip-in man bun to the launch of a ‘Man Buns of Disneyland’ Instagram account.

2015 was the year of the smart watch.

2015 was the year Oregon’s fanatic fondness for our 1980s-vintage airport carpet became all too clear.

2015 was the year of everyone being a whiny bitch.

2015 was the year of the Cool Bag.

2015 was the year that famous guys got on board with looking good – and we’re not just talking good in the suited-up, wingtipped way you might think (that’s so 2014).

2015 was the year of the neural network.

2015 was the year everyone you know and love abandoned you to move to Queens.

2015 was the year I discovered the wonder that is serum masks.

2015 was the year of the braid, which stepped out of its gym/beach/dirty hair/Pippy Longstocking confines and into the spotlight as a bona fide look for grown-up ladies.

2015 was the year of the drone.

2015 was the year we saw a lot more than we bargained for in terms of celebrity bodies.

2015 was the year menswear went back to basics, after years spent flouncing around in skinny suits and silk scarves.

2015 was the year everyone wondered why songs that weren’t ‘Hotline Bling’ existed.

2015 was the year that tech finally ate the festival.

2015 was the year I spent eleven dollars on a bottle of something that in any other circumstances would be a salad, and not even the kind of salad I would order.

2015 was the year of many things: hover boards, racist Presidential candidates dipped in dayglo and, most importantly, Uptown Funk viral videos.

2015 was the year that consumerism finally devoured the counterculture dream.

2015 was the year of oversized sushi.

2015 was the year Jane Fonda decided to remind the world that she still looks phenomenal in anything you care to put her in.

2015 was the year of armpit, but it was also the year where loads of people dyed it too.

2015 was the year of unearthed, painful memories.

2015 was the year of anti-everything.

Source: Google

Everyday life: a poem

Everyday life

Defy evil year

Everyday file

A fey delivery

I, everyday elf

Aide every fly

Every fly idea

Varied fly eye

Defy liver. Yea!

Delay free ivy

Live fey, deary

Livery eye fad

Levy dairy fee

Flare-eyed Ivy

Avid eye flyer

Fiery Lady Eve

Reedy ivy leaf

Leery, fey diva

Five-yearly Ed

Defy vile year

Devilry fee. Ay?

Early-feed Ivy

Fey drivel. Yea!

Everyday life

In defence of shyness

Here is Harold Nicolson writing ‘in defence of shyness’ in 1937:

‘Let us educate the younger generation to be shy in and out of season: to edge behind the furniture: to say spasmodic and ill-digested things: to twist their feet round the protective feet of sofas and armchairs; to feel that their hands belong to someone else …

For shyness is the protective fluid within which our personalities are able to develop into natural shapes. Without this fluid the character becomes merely standardized or imitative: it is within the tender velvet sheath of shyness that the full flower of idiosyncrasy is nurtured: it is from this sheath alone that it can eventually unfold itself, coloured and undamaged.’

The railway modeller as Ubermensch

I spoke at the launch of Stephen Knott’s book Amateur Craft as part of Liverpool Hope University’s Cornerstone Festival last week. Stephen’s book is about the pleasures of making but it is also about amateur craft as an industry: the market that developed from the late nineteenth century for artists’ sketch blocks, watercolour paintboxes, paint in tubes, prepared canvas, watercolour cakes, paint by number kits, toolboxes, portable workstations, poultry fattening pens and chick-feeding runs.

I particularly liked the chapter on model railway enthusiasts, and the pleasures of miniaturization:

‘The small scale of model train layouts situates the maker, or the operator of the model, as a God-like figure looking over all activities within view … Could we go as far as to say that the railway modeller is the closest realization of Nietzsche’s Übermensch, reaching the goal of “self-overcoming”? … Clearly not. The modeller’s God-like control is only a temporary affair that sits alongside a variety of less Nietzscheian activities and, like Superman who changes back itno the journalist Clark Kent, the modeller returns to an everyday persona.’

The fiercest joy

I wrote this about fishing on TV for the excellent Caught by the River site.

The best book I’ve ever read about fishing is Luke Jennings’s wonderful Blood Knots. Its description of the importance of the angler’s rites and rituals could also be applied to many other areas of our lives:

‘The rules we impose on ourselves are everything – especially in the face of nature which, for all its outward poetry, is a slaughterhouse. It’s not a question of wilfully making things harder, but of a purity of approach without which success has no meaning … the fiercest joy is to be a spectator of your own conduct and find no cause for complaint.’

The Ruins of the House of Boisterous Angus

In The Crofter and the Laird (1970), his account of returning to Colonsay, the tiny Hebridean island of his ancestors, John McPhee writes that on this island ‘almost every rise of ground, every beach, field, cliff, gully, cave, and skerry has a name. There are a hundred and thirty-eight people on Colonsay, and nearly sixteen hundred place names … The names commemorate events, revive special interests and proprietary claims of lives long gone, and sketch the land in language.’

McPhee goes on to provide some examples:

Gleann Raon a’ Bhuilg (The Glen of the Baglike Plain)

Sguid nam Ban Truagh (The Shelter of the Miserable Women)

Carraig Chaluim Bhain (Fair Malcolm’s Fishing Rock)

Carraig Nighean Mhaol Choinnich (Bald Kenneth’s Daughter’s Fishing Rock)

Pairc Aonghais Ruaidh (Red Angus’s Field)

Poll Eadar da Pholl (The Pool Between Two Pools)

Laosnaig Tonbhan (The White-Rumped Extremity)

Tobhtachan Aonghais an Dobhaidh (The Ruins of the House of Boisterous Angus)

The man who vacuumed his lawn

The Canadian poet-essayist Brian Doyle has written some powerful pieces inspired by 9/11. In his lyric essay ‘Kaddish,’ he captures the attacks on the World Trade Center by simply listing 217 one-line descriptions pulled from obituaries of the victims: ‘The man who occasionally vacuumed his lawn … The man who was identified by his Grateful Dead tattoo … The man who meticulously rotated the socks in his drawer for even use … The woman who loved pedicures on Sunday mornings … The woman who sketched commuters on the train every morning.’

In ‘Leap’, he considers the people who leapt from the towers from the perspective of onlookers: ‘They struck the pavement with such force that there was a pink mist in the air … Stuart De Hann saw one woman’s dress billowing as she fell, and he saw a shirtless man falling end over end, and he too saw the couple leaping hand in hand … I keep coming back to his hand and her hand nestled in each other with such extraordinary ordinary succinct ancient naked stunning perfect simple ferocious love.’

From Brian Doyle, Leaping: Revelations and Epiphanies (Loyola University Press, 2003))

Just another sense memory

I wrote this piece for last week’s Guardian about how the Amstrad PCW converted writers to the computer.

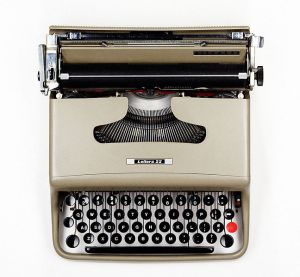

I suppose in the future mine will be remembered as the last generation for whom writing was an indubitably analogue act. We even had handwriting lessons in my primary school; at my secondary school they still had the old sit-up-and-beg desks that you opened up to put your books and papers inside, with a hole in the left-hand top corner for the ink well. I have no particular nostalgia for obsolescent writing tools like fountain pens or typewriters – unlike Will Self, who disdainfully calls the word processor the ‘plastic piano’ – although I do think the Olivetti Lettera (pictured above) was a thing of beauty.

But it is true that the act of writing is becoming invisible, the tools of the trade ethereal and fluid. Handwriting is now an endangered activity; after taking three-hour exams, my students’ arms ache, atrophied by technology. We are forgetting writing’s associations with the impression of ink on page. How much longer will computers even have keyboards? You never hear the labour of writing any more – except in our university library, where the quiet patter of a hundred keyboards sounds like gentle rain hitting rooftops. Perhaps writing in the future will simply be a matter of touchscreens and voice recognition. ‘Typing may someday survive only as another sense memory,’ wrote Marshall Jon Fisher in his 2003 essay ‘Memoria Ex Machina’. ‘A writer, while composing with his voice, will still tap his fingers on the desk like an amputee scratching a wooden leg.’

Shrinking violets

I’ve just finished a book called Shrinking Violets: A Field Guide to Shyness. ‘Shrinking violet’ is not, in fact, a phrase heard much these days: along with the word ‘wallflower’, it has a pre-1960s feel to it. In Howard Jacobson’s autobiographical novel The Mighty Walzer, the Shrinking Violets are the central character’s shy aunts as described by his father, who refers to them as if they were ‘an established showbiz group like the Andrews Sisters’. (Jacobson, by the way, has described himself as an acutely shy child who became a writer ‘because I was afraid of the world and wanted to remake it’.)

A Google search for ‘shrinking violet’ today brings up links to a weight reduction method that women may use to magically ‘reduce by a dress size in one treatment’. It seems to involve wrapping oneself in a heat-inducing cling film-type material full of essential oils that trigger lipolysis, which breaks down fats so they can be processed by the liver. It promises, in other words, a literal rather than a figurative shrinking – the only type of shrinking now deemed acceptable in a society ruled by what Susan Cain calls the ‘extrovert ideal’.

Someone once suggested to me that writing a book was like dropping a stone down a really deep well. The stone might rattle along the sides of the well’s walls a bit, to remind you of its continued existence, and then years later you might hear the tiniest plop as it hit the water table. I think the metaphor was meant to be consoling, to remind you never to give up hope of a long-delayed response to your work. But instead it made me worry that writing was a one-sided and fluky affair, with no guarantee that it would ever find a reader. Anyway, I have thrown in my stone, and I will come back in a year to see if I can hear a little splash.